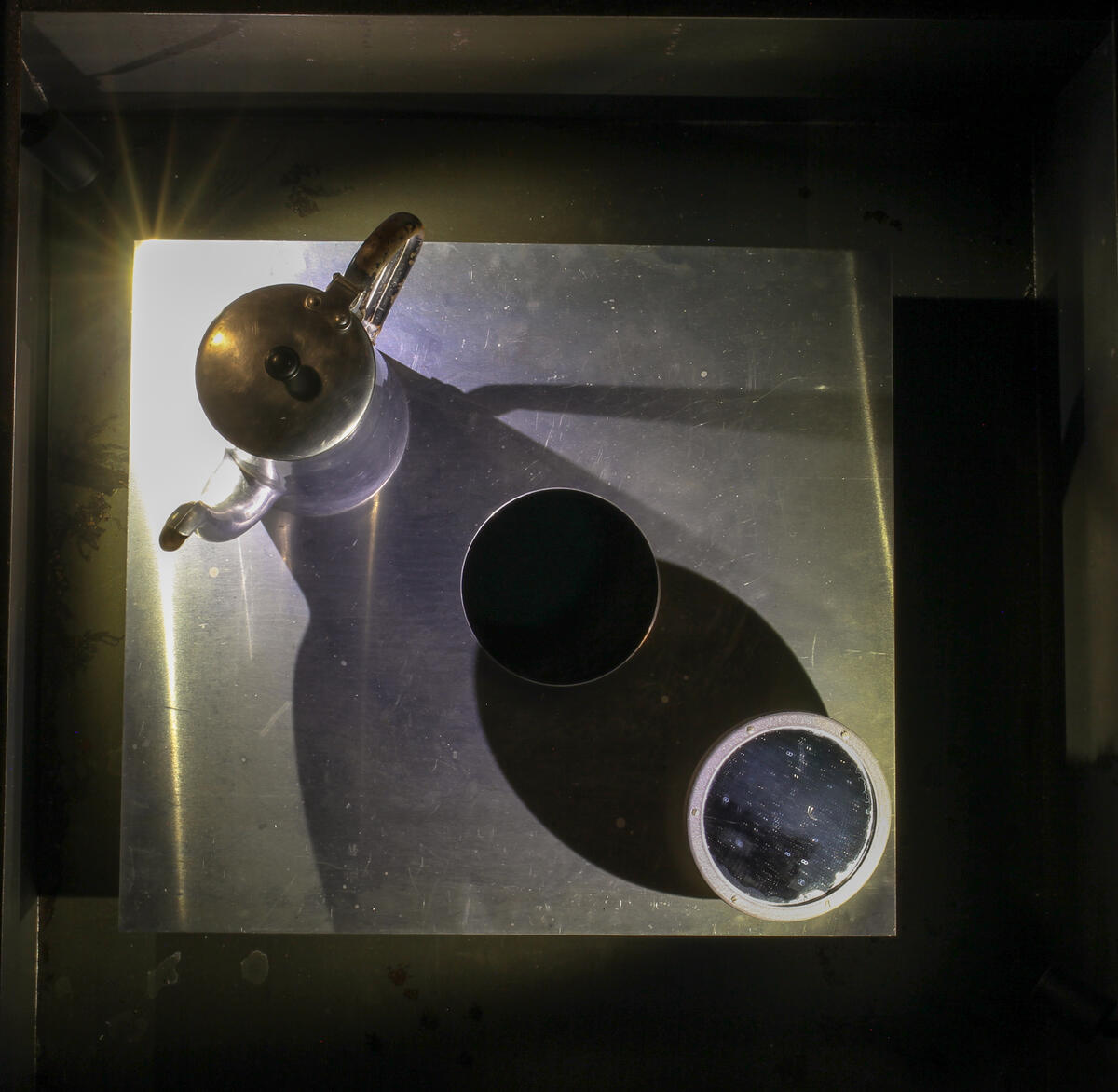

1.

Aluminium production on an industrial scale began in Norway, several new companies were established to refine the raw material into manufactured goods. Kitchenware turned out to be an efficient spearhead in the campaign to convince consumers of this modern material’s impressive properties.

From the early 1920s on, Nordisk Aluminiumsindustri‘s Høyang brand vied with Triangel from Norsk Aluminiumvarefabrikk in Bergen, Il-O-Van Aluminiumvarefabrikk in Moss, and Halden Aluminiumvarefabrikk in offering the most desirable aluminium pots and pans to households across the country. In the early phase, the design of the products was not particularly original, but rather followed the conventions established by similar objects made from other materials.

This coffee pot is a good example of this practice, where aluminium is literally snuck into homes through the kitchen entrance.

2.

In the interwar years, aluminium was a new and modern metal, perfectly suitable as a medium for the core values of modernism, such as technological progress, efficiency, standardization, and hygiene.

This coffee pot, which remained in production from c. 1935 to the late 1960s, illustrates how aluminium in this period became the preferred material in the kitchenware industry.

The functionalistic design ideals of the day, promoted e.g. by the Norwegian Applied Art Association’s extensive exhibition and publication program, and the scientification of housework, which culminated with the establishment of the National Institute of Home Economics in 1939, converge in objects such as this. Accordingly, aluminium kitchenware was in this period marketed using a rhetoric emphasizing qualities such as economy of space, energy efficiency, and cleanliness.

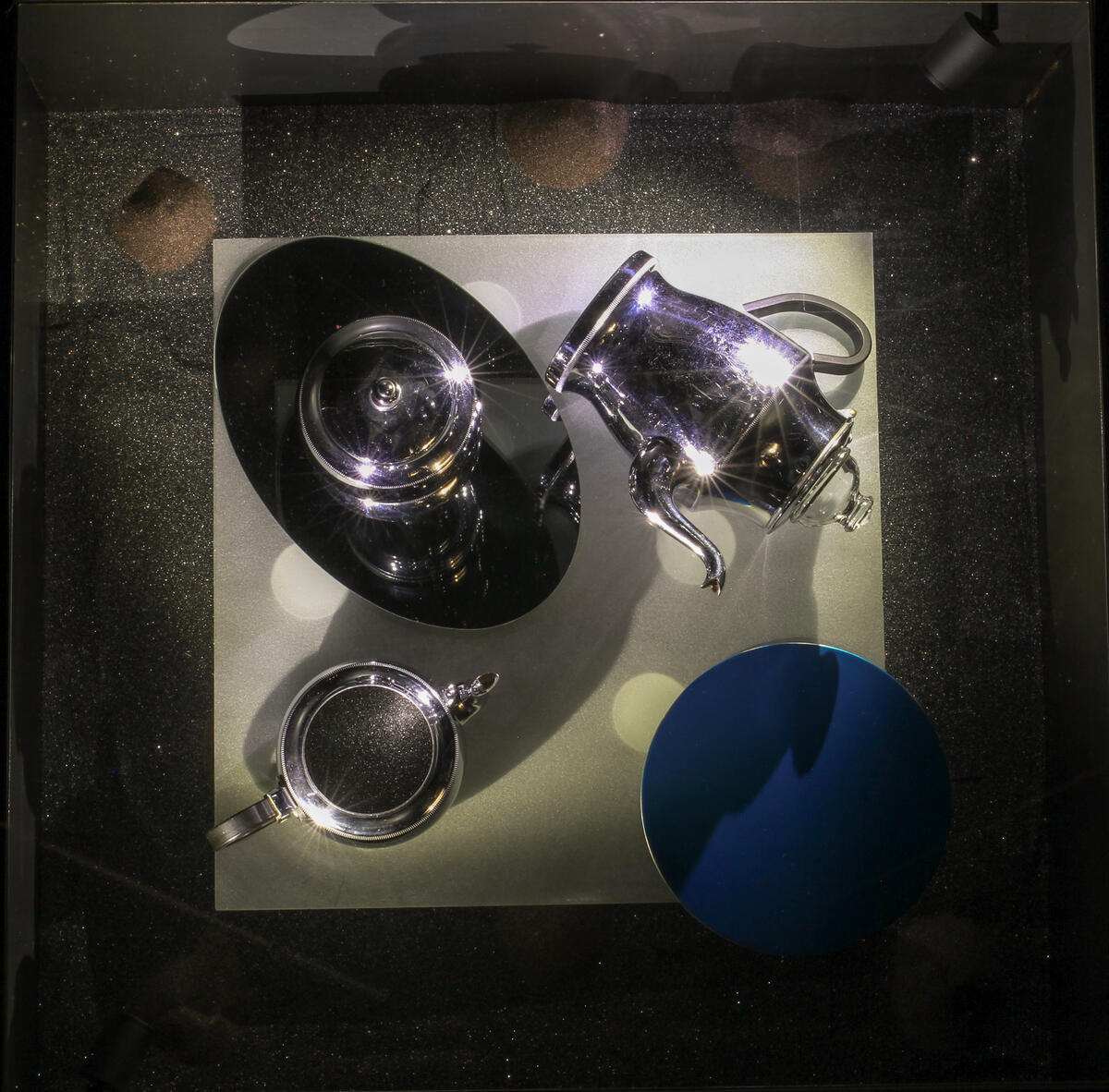

3.

The surface treatment known as cromalin significantly changed the character of aluminium products.

The shiny surface symbolized cleanliness, newness, and glamour, and made aluminum product look like objects made from far more exclusive materials such as silver and stainless steel.

Later on, other techniques would in similar ways “beautify” the otherwise dull-gray surface of aluminium. This became increasingly important as the material itself lost its novelty, but had become the new standard.

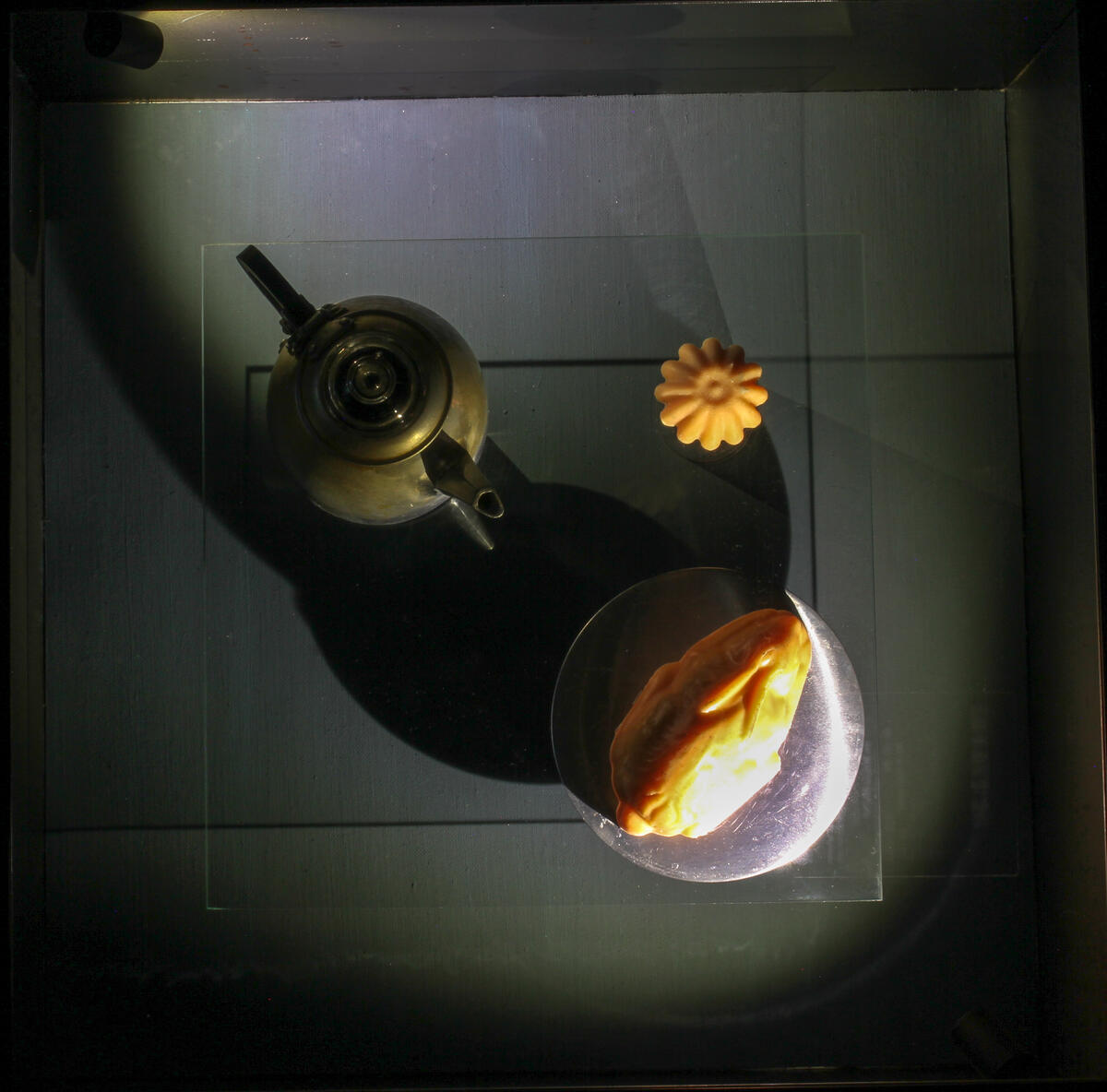

4.

Kaffeperkolatorer ble produsert i enorme mengder fra 1930-tallet. De ble mest brukt fram til 1970-årene, da de ble erstattet av kaffetraktere og forsvant fra markedet.

5.

With increased maturity and greater competition amongst the companies, the aluminium industry faced a growing need for professional design expertise, which in turn resulted in far more refined products.

This elegant, well-proportioned cooking pot, with exquisite design and detailing, is designed by illustrator and brazier Ingeborg (Ingse) Gude Folkestad.

A cromalin version was, alongside a coffee set in the same design, shown at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. This exhibition, under the optimistic and progress-idealizing motto “The World of Tomorrow”, featured other Høyang products as well, including frying pans designed by goldsmith Oskar Sørensen, who would become the company’s most important designer for decades to come.

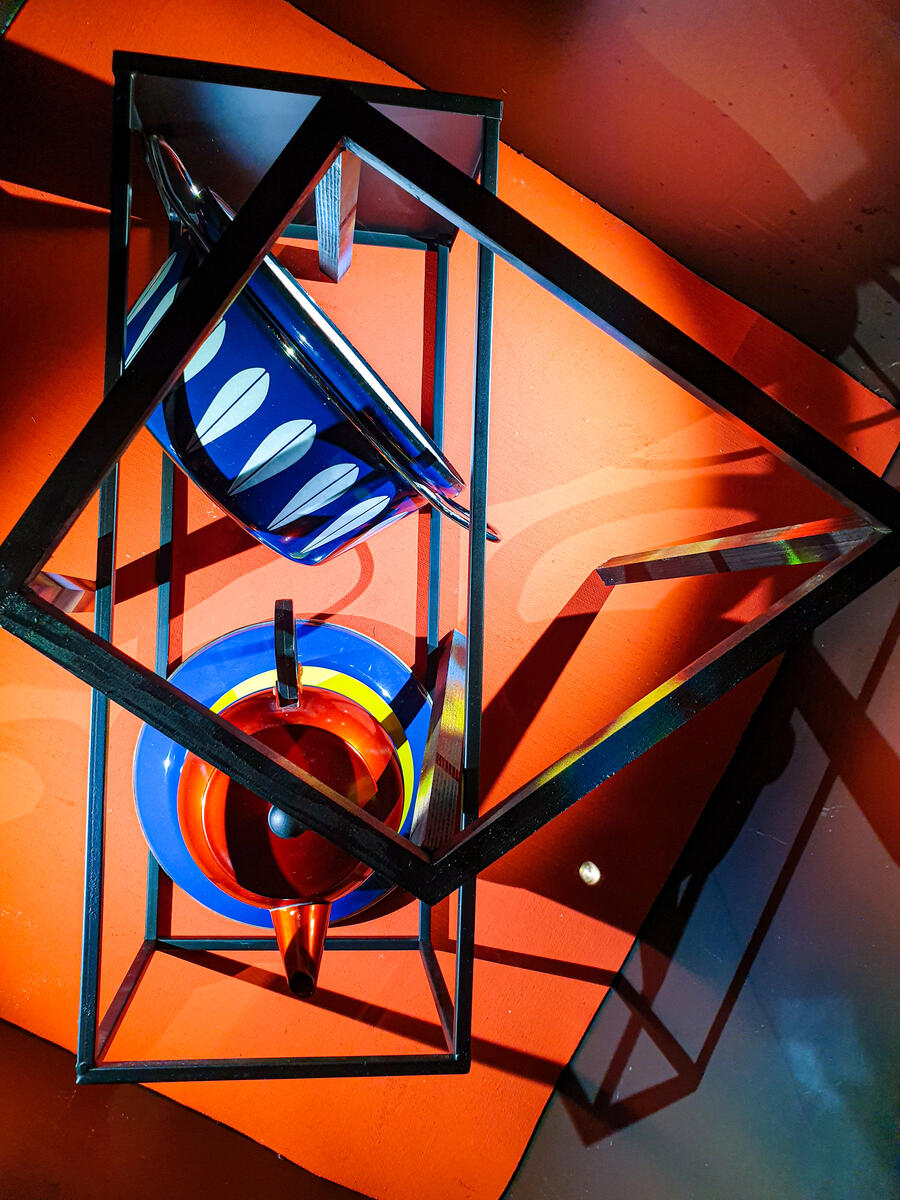

6.

The professionalization and specialization of the product development processes continued in the postwar period, both at Nordisk Aluminiumindustri and at its competitors, reflecting the consolidation of industrial design as a profession in its own right, partly in opposition to the established concept of applied art.

These bowls from the late 1950s are designed by Grete Prytz Kittelsen, who was a key figure in this transition. As a goldsmith in the family business, J. Tostrup, she designed both exclusive exhibition pieces to cheap enamel jewelry manufactured in series, but on a freelance basis she also designed industrially produced goods such as those shown here, as well as the more well-known bowls, dishes, pots, and pans in enameled steel for Cathrineholm in Halden.

These aluminum bowls were intended as giftware, and thus exemplify a marked expansion of the product range from the interwar period’s clear focus on the tools of the housework trade to include also products where the aesthetic and symbolic functions are at least as significant as the utilitarian ones.

7.

After almost twenty years as freelance designer for Nordisk Aluminiumindustri, goldsmith Oskar Sørensen resigned from his position at J. Tostrup in 1957 in order to devote himself to designing Høyang products on a full-time basis.

One of the first results of his new role was this “luxury coffeemaker”, which clearly demonstrates Sørensen’s characteristically elegant shapes. It is also a good example of how the anodizing technique in the 1950s transformed aluminium kitchenware from something grey and matte to something colourful and shiny.

8.

Nordisk Aluminiumindustri eventually became the dominant actor in the market, and Høyang the strongest brand. But Il-O-Van gave them a good run for their money, and their strongest card was the so-called “Pouring Kettle” introduced in 1951.

This coffee pot, designed by Thorbjørn Rygh, became extremely popular, to their competitors’ frustration and inspiration alike. Here it is shown alongside Oskar Sørensen’s competing coffee pot from Nordisk, launched in 1960, even in the same pink anodized execution.

That same year, Nordisk established a sales and marketing agreement with Il-O-Van (as well as Halden Aluminiumvarefabrikk and Norsk Aluminiumvarefabrikk (Triangel)), and from 1968, its kitchenware division was merged with Il-O-Van, with Høyang as the common brand.

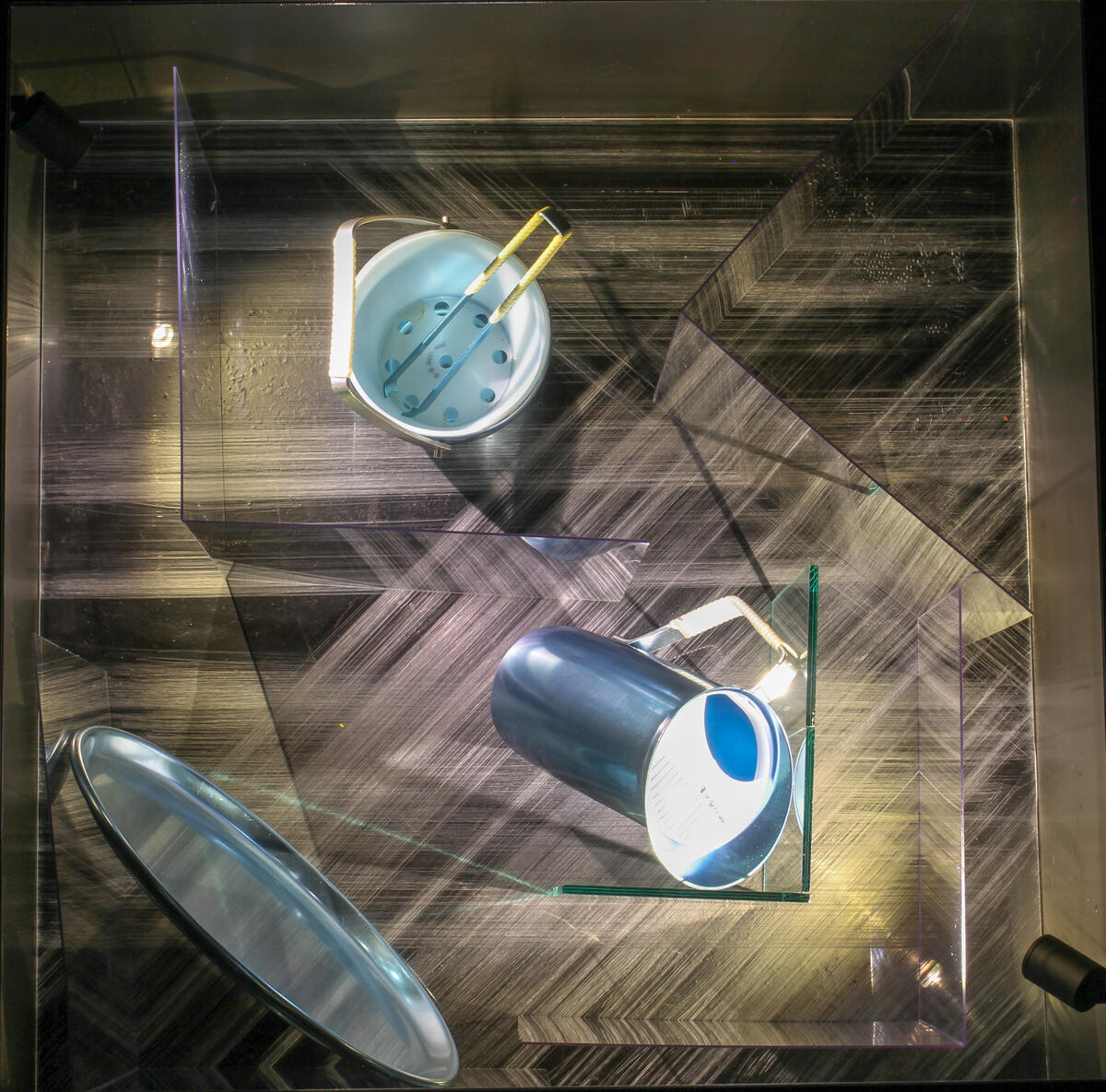

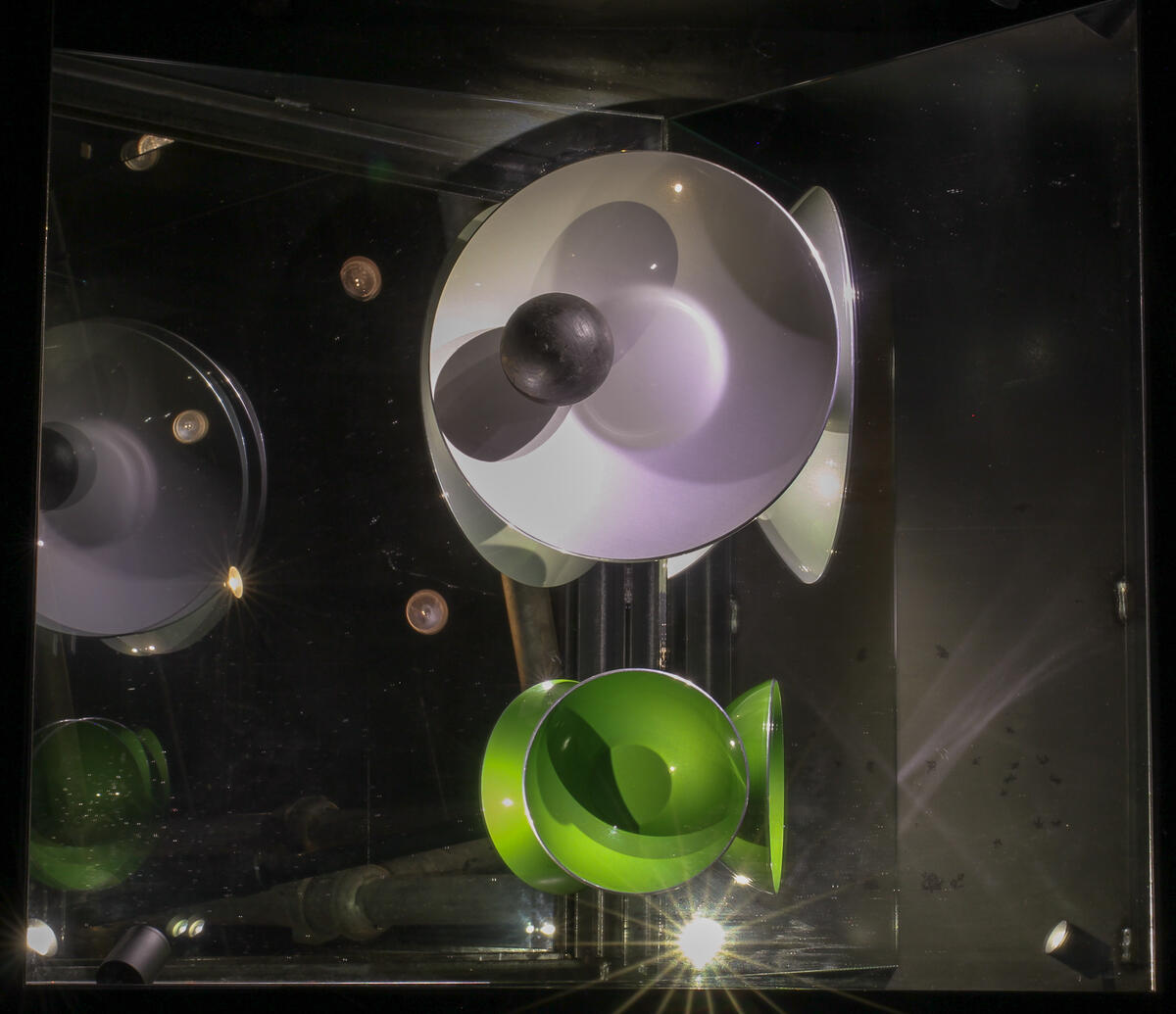

9.

The rationing systems and the reconstruction mentality which characterized the first postwar years were succeeded by a far more hedonistic consumer culture from the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, stimulated by strong economic growth.

Increased spending power combined with improved welfare policies, as well as shorter working hours and longer vacations, provided a breeding ground for a new leisure culture. This provided the Norwegian aluminium industry with new markets, to which it catered by offering anything from picnic sets and camping equipment to small leisure boats for nature lovers, but also products intended for more continental leisure practices, such as this bar set from 1957 designed by Oskar Sørensen.

Consisting of a jug, ice bucket, tongs, and serving tray, this stylish set represents a cool elegance and a social status far removed from the prosaic juicers and fish pans which dominated the product range just a few years earlier. Both the underlying design process, as well as the design culture of which the bar set and similar products became part, thus contributed to transforming the meaning of the material.

10.

Il-O-Van’s “pouring kettle” from 1951 is an exquisite piece of industrial design by one of the field’s true pioneers in Norway, Thorbjørn Rygh. As the name implies, it was designed for easy and spill-less pouring, with special attention to the detailing of the spout, optimal distribution of weight, and an ergonomically shaped handle.

Originally executed in polished aluminium combined with an anodized lid, it sold well from the get-go, but only upon the launch of an all-anodized version in the late 1950s did sales truly take off. Reaching annual production runs of c. 100,000, it remained in production for twenty-five years, until 1976. Rygh also designed Bakelite saucepan handles for Il-O-Van. He co-founded the professional organization Norwegian Industrial Designers in 1955, and later became Norway’s first professor of industrial design.

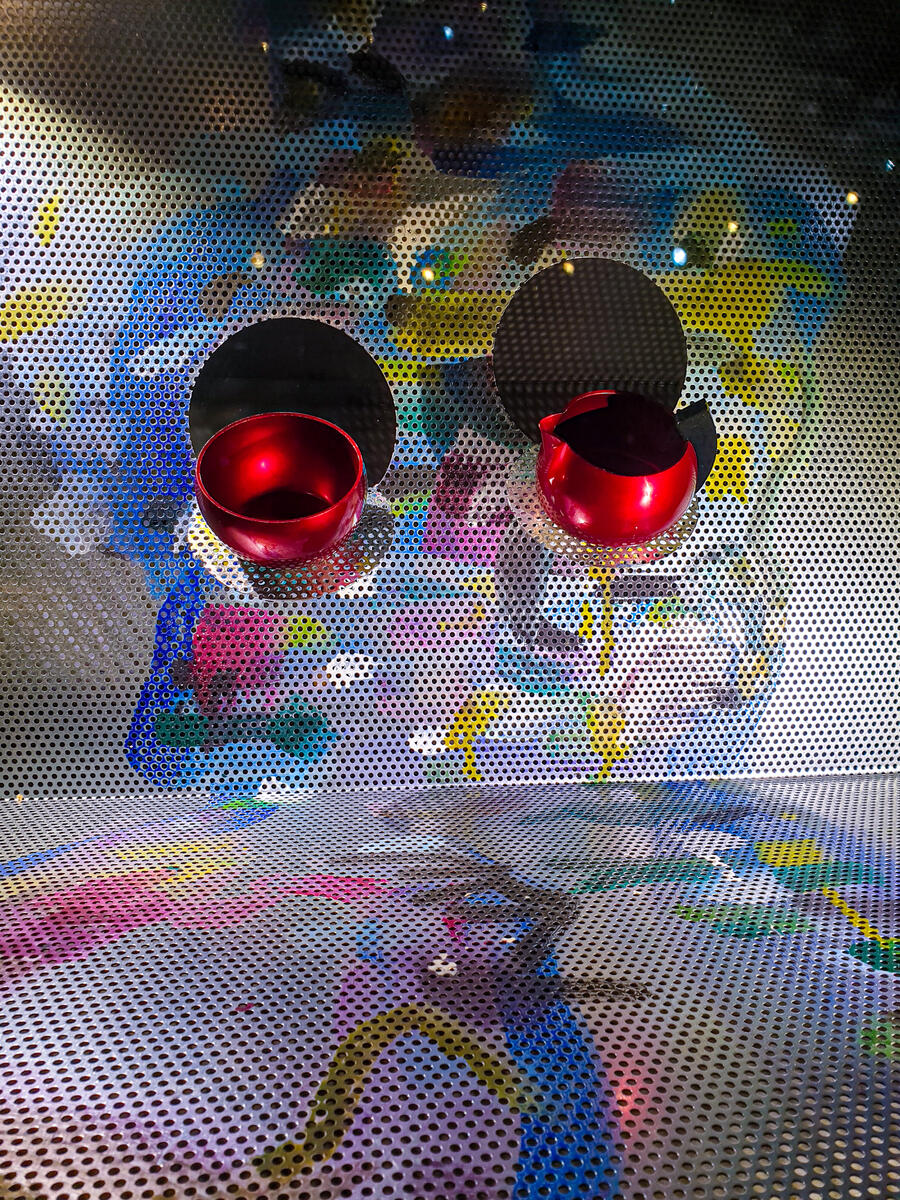

11.

This sugar and cream set from Il-O-Van was launched as an accessory to the “pouring kettle”, in the same, rounded design and the same anodized execution.

12.

The «cocktail culture’s» emphasis on elegant presentation rubbed off also on the dining table, as seen in these covered dishes from around 1960.

13.

The impact of continental eating and drinking habits on Norwegian dining tables grew significantly during the 1960s, changing also the accompanying material culture, as exemplified in this wine cooler from Halden Aluminiumvarefabrikk.

At the same time, aluminium’s hegemony in the kitchenware industry was challenged, especially by increased competition from stainless steel, as in this ice bucket. Designed by the Danish designer Adam Thylstrup and manufactured by the Swedish company Nilsjohan, it also illustrates other challenges faced by the Norwegian consumer goods industry in this period.

International free-trade agreements, and particularly the EFTA treaty of 1960, made import restriction and toll barriers fell like dominoes, resulting in much greater competition from foreign manufacturers also on the domestic market.

14.

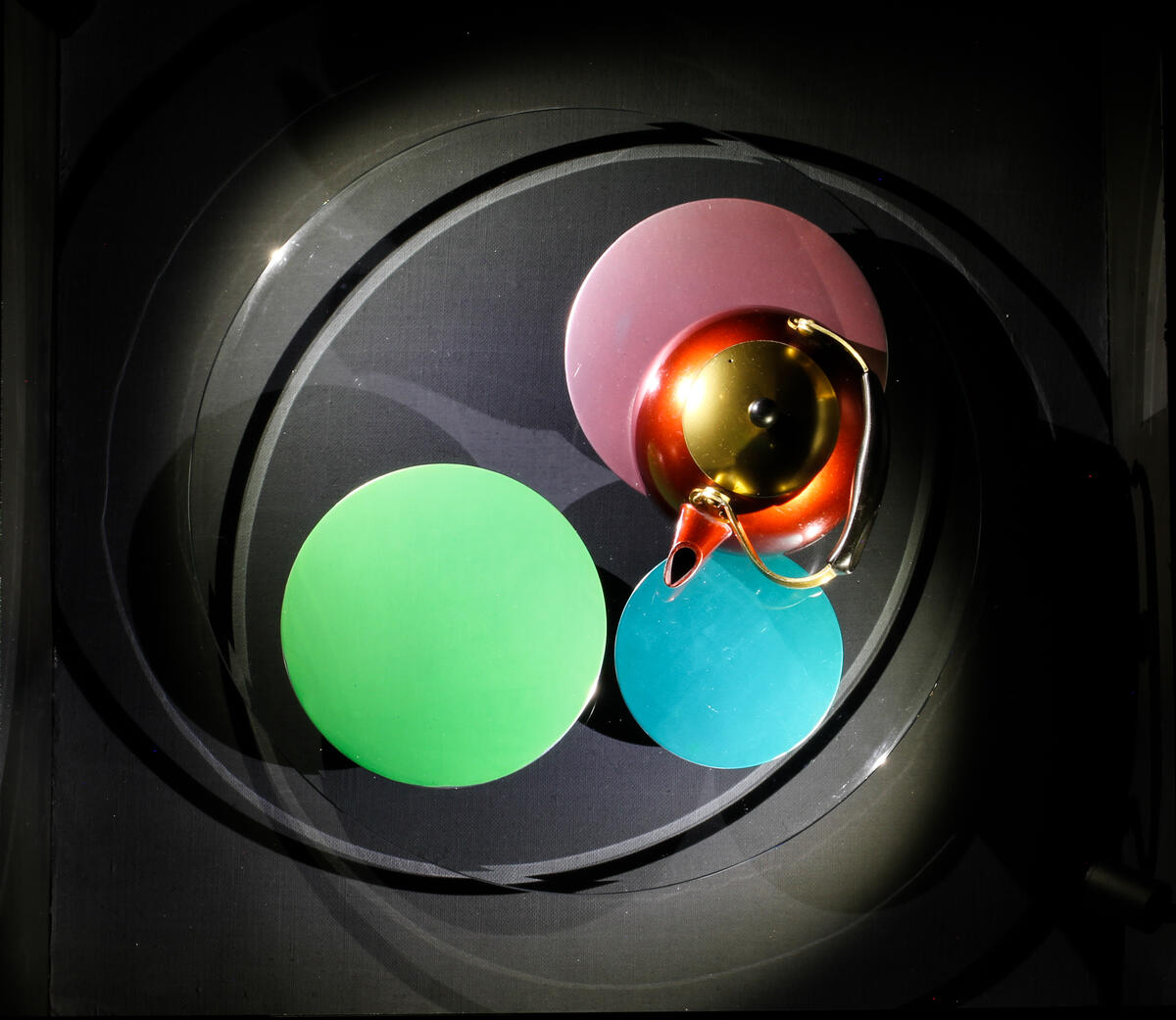

Basic tableware such as bowls, dishes, napkin rings, vases, etc. made from very colourful anodized aluminium became something of a fad in 1950s Norway. Anodizing, achieved by immersing the aluminum into a coloured acid electrolyte bath and passing an electric current through the medium, turned out to be an efficient way of making affordable, mass-produced goods attractive.

The shapes of the goods were simple and unadorned, but the colour itself became a decorative feature. Most well-known amongst the many enterprises which jumped onto this bandwagon is Emalox, which was later acquired by Nordisk Aluminiumindustri.

The bowls shown here are part of a wide range that Bjørn Engø designed for the company from 1955 on, which with their elegant forms and brilliant colours became a hit both with consumers and with design professionals. It won a silver medal at the Triennale di Milano in 1957 and received the Norwegian Design Centre’s Mark of Design Excellence in 1968 – completely in line with Engø’s aim of creating “affordable products of good design”, as he explained to the design magazine Bonytt.

15.

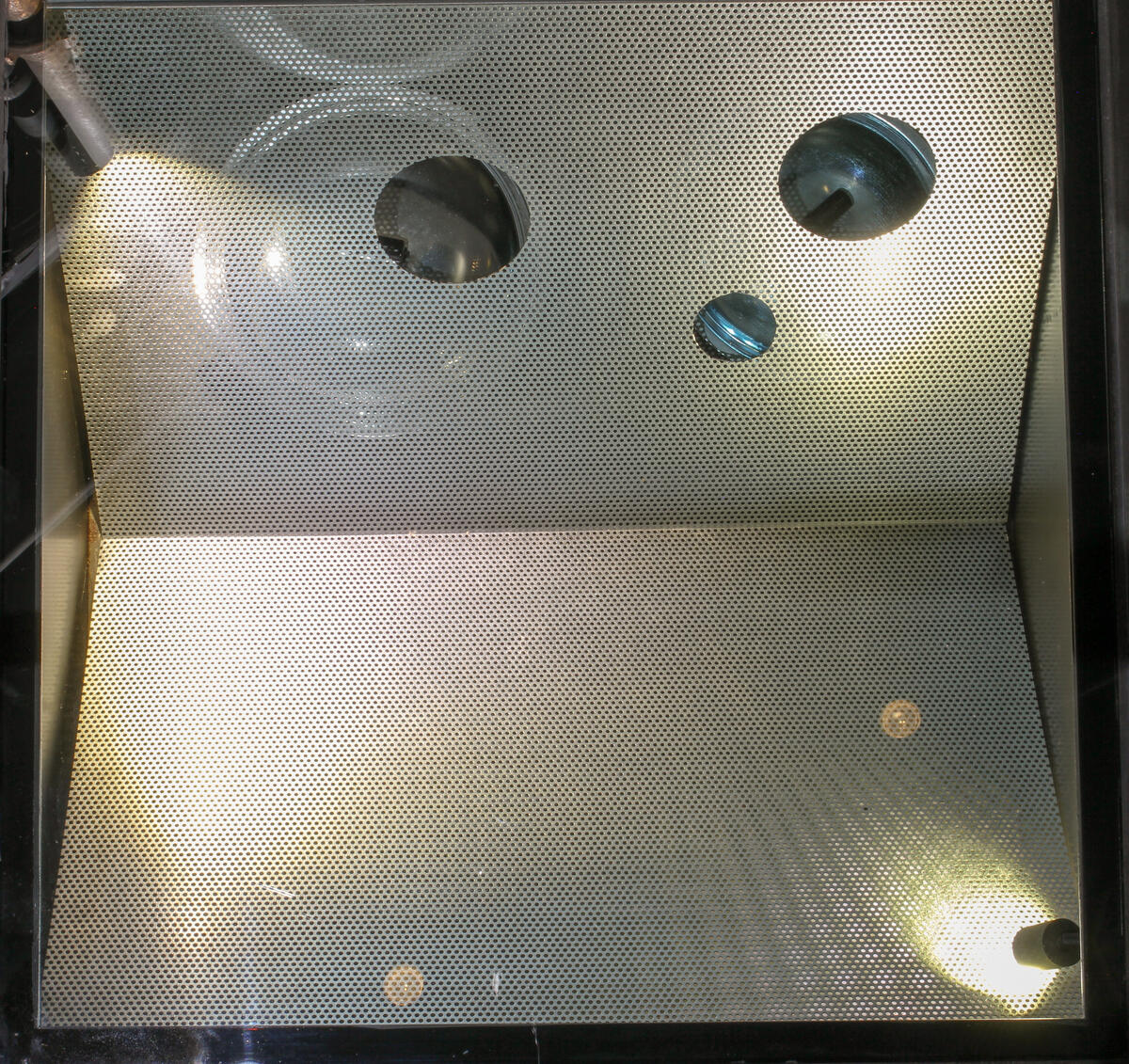

One of the strategies deployed in the competition from stainless steel, was to imitate the newcomer’s visual properties. The cooking pot series Høyang Extra from 1962 promises, as the name says, something beyond the ordinary aluminium product.

Executed in polished aluminium, Extra shines as brightly as stainless steel, almost like the cromalin products from the interwar years. The series was designed by Oskar Sørensen, and when it was awarded the Mark of Design Excellence in 1967, it was described as characterized by a “simple, sober, somewhat fashionable design”.

Extra featured prominently in a marketing campaign from the mid-1960 under the slogan “The Future Chooses Aluminium”, in which both product design, graphic design, and illustrations all contribute to the manufacturer’s staunch effort at elevating aluminium goods to design culture’s higher echelons.

16.

Disse skålene er også er en del av det brede varesortimentet til Emalox designet av Bjørn Engø.

17.

In addition to stainless steel, another, and perhaps less expected competitor entered the playing field in the shape of some particularly well-designed and well-marketed products made from enamelled steel when the Halden-based enamelled steel manufacturer Cathrineholm in the mid-1950s modernized their operations and expanded the product range from wash-bowls, waterjugs, etc., to include also cooking pots, coffee pots, bowls, dishes, etc.

New enamels were developed in collaboration with the National Institute for Industrial Research and Hadeland Glassworks, tailored to a broad, new product range designed by Grete Prytz Kittelsen.

The collaboration with Kittelsen continued for many years, and one of the most popular results is the so-called “Sensational Pot” from 1962, here shown with the Lotus patterns introduced in 1965, designed by Cathrineholm’s own designer, Arne Clausen. Despite the popularity of these new enamel products, they could not save the company, which folded in 1970.

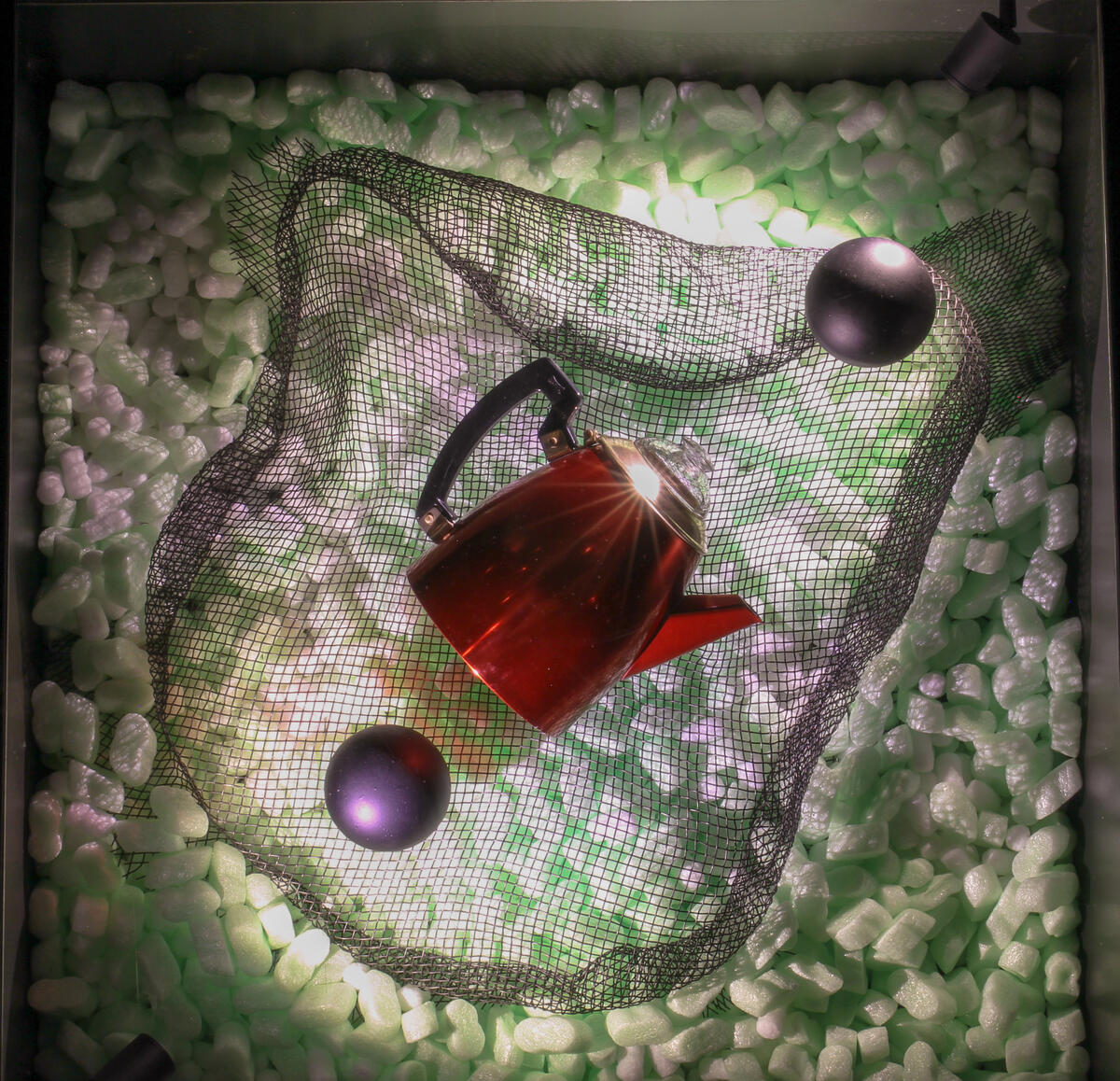

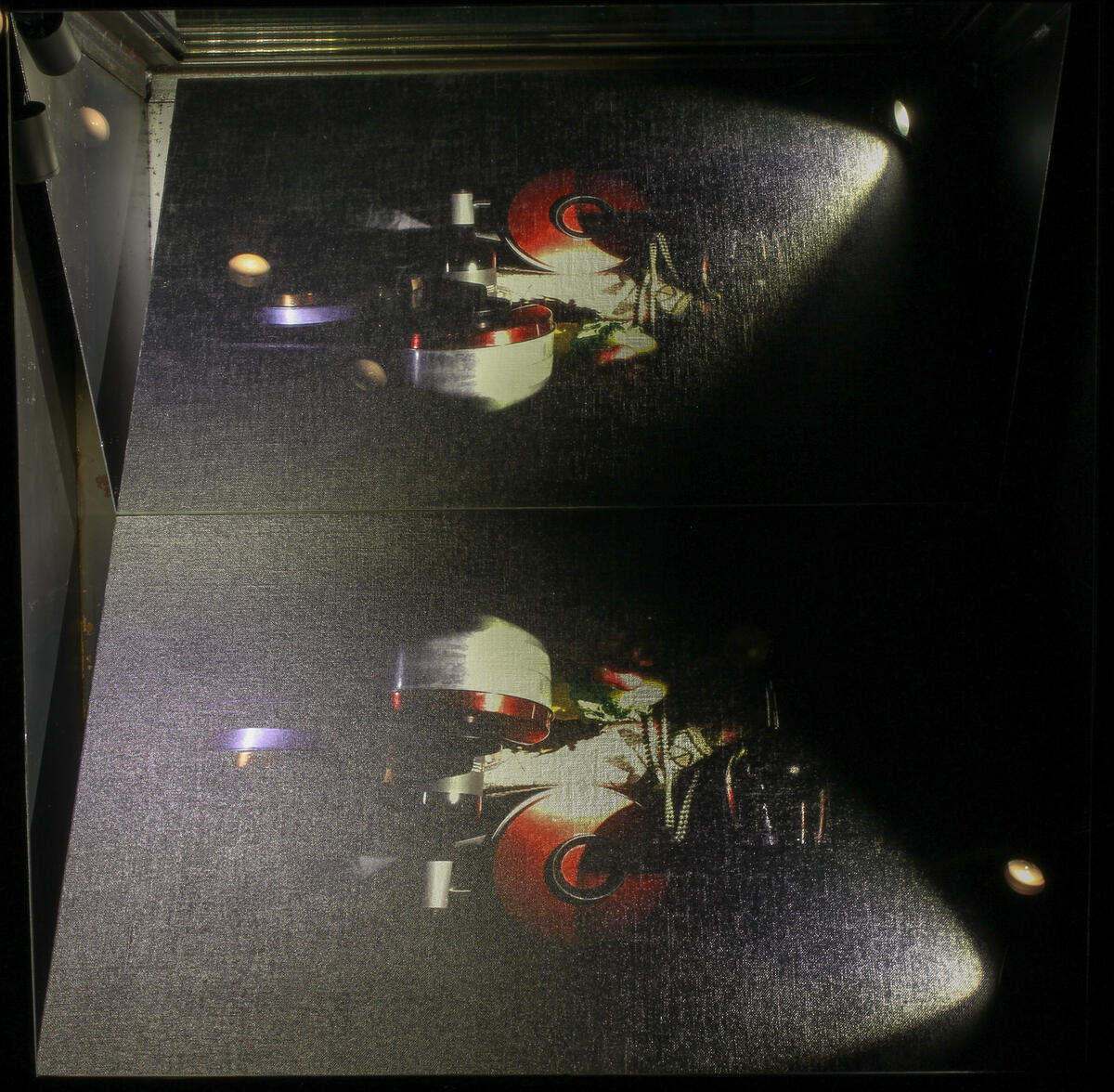

18.

The battle between aluminium and steel intensified toward the end of the 1960s, as the former’s position was weakened by worries over potential health hazards caused by cooking food in aluminium pots.

Here we see a Høyang coffee pot designed by Oskar Sørensen in the characteristic red anodized execution, face to face with the competitor in stainless steel from Sandnes-based Polaris, designed by Olav Joa around 1966. At the same time, the competition from foreign manufacturers also increased, resulting in changes to the ownership structure across the sector, as in the rest of the Norwegian consumer goods industry.

In 1967-1968 both Nordisk Aluminiumindustri and Il-O-Van were acquired by Årdal og Sunndal Verk, which in turn, in 1975 sold the kitchenware division to Polaris. The battle between aluminium and steel thus ended in something of a truce, and the Norwegian kitchenware industry was reduced to one company and one, common brand, Høyang-Polaris.

19.

At the dawn of the 1970s, simply offering something “Extra” could not make aluminium kitchenware sufficiently desirable.

Enter Høyang Luxus, a new range based on the shapes of the Extra series, but where the once so “rational” and “honest” aluminium was dressed up beyond recognition to increase its status: the pieces’ insides coated with Teflon and their outsides cloaked by fashionably coloured enamel.

The inside of aluminium pans, which used to be hailed for being practical and hygienic, now had to be covered up for failing in the very same departments: Teflon was to keep food from sticking and to keep aluminium – now considered a health hazard – from infecting food during cooking. The outside of aluminium pans, which “nudity” used to be flaunted as an expression of economy and progress, now had to be hidden from view by means of a decorative technology hitherto reserved for more ‘precious’ metals like steel and silver. The only quality left for aluminium to boast about was its heat conductivity.